Kidney transplant recipient and successful Transplant Games competitor, Murray Beehan, tells his story below. Read, in his own words, about the treatment that he has received and what it meant to him to compete in the Transplant Games.

Firstly, thanks for taking time to read my story. I am Murray Beehan, I have struggled with bouts of ill-health my entire life, however, the story begins before I was born.

My mum was an average-sized woman, I on the other hand had grown to the over-average weight of 8lbs 14oz.

On an unusually mild, wet and windy December in 1986, I decided it was my time to greet the world, however, my larger than average size caused me and my unfortunate Mum to go through an excessively difficult childbirth. So difficult in fact, that I went into shock.

The shock I suffered, caused what is known as ‘bilateral renal thrombosis’, it’s a technical term for a blood clot in the veins connected to the kidneys. The clot then prevents or limits blood from draining away from the kidneys, resulting in reduced kidney function. The usual outcome for a neonatal patient would be, either; make a full recovery with no lasting damage or to not survive. I somehow chose the very-rare third option, surviving with almost no measurable kidney function. Incredible, I know.

And so the story continues. Fast forward two weeks, I was just about to become the first ever child (under the age of two years old), to be dialysed by Birmingham Children’s Hospital (BCH).

In those archaic times, dialysis fittings that were suitably small enough did not exist. What was the relatively simple solution? To attempt the creation of a makeshift peritoneal dialysis kit. It oddly included a gallipot (a posh word for a pot that pharmacists use to hold medicine), it was used to stabilise the various needles and tubes protruding from my abdomen that were needed to perform dialysis.

The paediatric renal team dialysed me for one week - they did not anticipate it would work. It did, it worked perfectly. By the end of the week they had removed all the fluid, right down to my dry weight (a bodyweight at which there is no excessive fluid retained). At that point, I was handed back to my Mum and Dad, and discharged.

You’re probably wondering why this happened?

For a number of reasons the paediatric renal team did not think the makeshift dialysis would work long term. I was not physically developed enough to receive a transplant, and it was highly unlikely that I could be fed enough to develop me, considering all the dietary restrictions I was under. My parents were told to go and have as much quality time with me as they could, as I was not expected to survive more than ten days.

Against all the odds, I didn’t just survive, I thrived to 18 months old. BCH agreed to take me back for treatment, as I had surpassed all expectations. I was treated with peritoneal dialysis (once more) to stay alive and had a special diet to help support my growth. I was severely restricted on free flowing fluids. I guess at this point you must be wondering, how did my parents satisfy my thirst? They were allowed to either; let me suck on a wet flannel or an ice cube. I was predominantly kept hydrated via my overnight feed.

At aged two, after 6 months of peritoneal dialysis and its associated restrictions, I had finally grown enough to attempt my first kidney transplant, however, after only one week I suffered an infection of my peritoneum and the surgeons were forced to open me back up, remove the transplanted kidney and flush out the infection internally. This, unbeknown at the time, would cause me significant issues later on in life, but it also had the immediate effect of saving my life. Due to the damage caused to my peritoneum, I had to start haemodialysis; it meant I could no longer do dialysis at home.

As there was no facility for children to receive dialysis in Mid-Wales (at the time of writing this there still isn’t), I dialysed in Birmingham three times a week, for four hours each time, not including the travel time of two and a half hours each way. This palaver lasted a further 12 months until, aged three, I was called up for a second transplant.

Again, I had a ridiculous amount of bad luck and the transplant did not work from the get go - it clotted.

Following the multiple kidney transplant failures, my parents had a haemodialysis machine plumbed in at home, they were taught how to do the treatment and I was able to perform the dialysis, three times a week, after school.

I wasn’t placed on the transplant list again until the end of 1991, aged 5. Miraculously a month later, at the end of January, my parents were given the call to say a match had been found for me. The transplant worked.

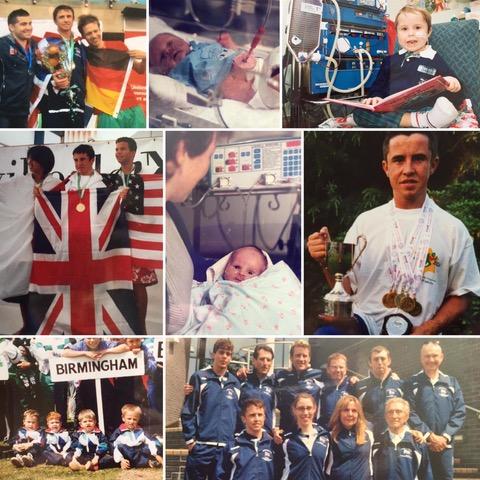

In 1992, my parents received guidance from one of the paediatric renal nurses (Jessie) at BCH, I attended my first British Transplant Games in Exeter. It was to help form a healthy lifestyle and promote recovery.

I was a fairly successful athlete and often brought home medals. It wasn’t just about the medals. Sure, winning medals was a significant driving factor, but I also enjoyed being amongst children who had gone through similar life experiences.

I had plenty of friends in my hometown, but none of them really got it. What it was like to have a transplant, to experience ill health, to take medication every day, to experience the side effects. This list could go on, but at the games I wasn’t different. I fitted in. The friends I have made at the transplant games have become lifelong friends, who I see year in year out.

The games encouraged me to live a healthy lifestyle. I wanted to attend the games every year and wanted to do well, I luckily found sport fun and I used that to my advantage. Training wasn’t taxing; it was something I looked forward to.

Similarly the same could be said for my family; Mum and Dad were able to meet other parents that had also gone through similar experiences, and my brothers were able to meet other transplant siblings. It had become a source of both enjoyment and therapy. We continued to attend every year.

By 2003, at age 16, after a successful British Transplant games, I was selected to represent Team Great Britain and Northern Ireland, at the World Transplant Games in Nancy, France - a children’s team had never before been invited to the World Games - me and the 15 other children gladly accepted the selection and proudly represented our country. Many of us, including myself, took home our first (the first) World Transplant Games children's medals.

In 2005, aged 18, I took part in the World Transplant games in London, Canada. Again, I took home some more medals.

In the same year, I began my studies at Cardiff University, and during this time I did not attend any World Games. I Graduated in 2009.

In 2013, I attended the world games in Durban, South Africa and I brought home a further gold medal in swimming.

By 2016 I was starting to experience ill health again. You may recall, at two years old, I suffered with an infection of my peritoneum. 28 years later, it resulted in me experiencing reoccurring bowl twists. I was told that surgery would be the last option as any procedure of that magnitude would ultimately cause my transplant to fail. I managed to hold off a number of times, but finally there was no other option. I had to have surgery. The surgery saved my life (again) but my transplant failed.

In April 2018, I started haemodialysis. I held off as long as possible, but it was increasingly clear I needed medical intervention. I couldn’t walk, I couldn’t stand long enough to brush my teeth or hair, felt constantly sick, and slept much of the day and night. I am dialysing three times per week, four hours a pop at my local hospital.

For those of you who are wondering, how long did my transplant last? It was between 26 and 27 years. I often get the question of: what’s the secret to keeping a transplant? I can only put it down to three things, religiously taking my medication, full engagement with all medical teams and last but certainly no means least, a healthy lifestyle of exercise and eating a balanced diet.

The best investment you can do is the investment in yourselves, engaging with physical activity and healthy eating will go a long way to keeping your transplant happy. Participating in the British Transplant games will give you a platform to showcase what you are capable of, and to promote the benefits of transplantation to the wider public. Being part of the team will give you a group of people who will - undoubtedly - become lifelong friends and a source of support.

Murray Beehan, March 2019